For a long time I have wondered what distinguishes a great story-teller from the rest. Clearly, great story tellers are blessed with great creative skills and imagination. Many of the basic techniques of writing such as structuring, using dialogue, grammar, point of view, and voice, can be learnt. The creative skills of story telling are much more difficult to develop, but not impossible. The first stage is to find the concept or idea from which you can develop a story.

The great concept or idea

All great stories start with a great concept. What if there is a school for wizards? (Harry Potter). What if a dystopian society forced children to kill each other in a tournament for entertainment? (Hunger Games). What if a cop waiting for retirement is paired off with a partner with suicidal tendencies? (Lethal Weapon). What if a plane carrying the president is hijacked? (Air Force One).

But how do you find these killer ideas? The answer is to find that one great idea you need to generate lots of ideas, most of which will be rubbish. But eventually you will find that gem that stands out from the rest. The first step is therefore idea generation and here are some of the techniques that can help:

- Day dreaming – I do this a lot. What if… an alien artifact was found in your garden… What if a new cold drug remedy had the side effect of giving autistic children mind reading powers… Good ‘what if’ questions will almost always lead to further questions to hone the concept further. Write down your ideas however silly they seem. Let them germinate with time and grow. Revisit the ideas after a passage of time and you might see them in a different light.

- Collecting odd ideas – from news and other sources in a journal/notebook. Ideas that are not written down will be lost. Don’t lose them.

- Turning an existing story idea on its head. What if the antagonist is really a good guy after all? What if the macho male hero is a child, a female, a seventy-year old, a paraplegic, someone with OCD. How does the story change? What if the ending was changed into a tragedy?

- Combining ideas from different stories into something new. A love story and titanic. (Sorry, that’s been done). Die hard on a battleship. (Sorry, that’s been done too.) Die hard on the Titanic? Sounds crazy…. change it. Die hard on a nuclear submarine… Keep changing it until something works.

- Free writing. Just write with a pen and paper, what comes into your head for ten minutes without stopping to think. Believe me, it works. It helped me find the idea behind my debut novel. You will write a lot of rubbish, but it is the precious gems of wisdom within that rubbish that you can salvage and use.

- Idea association: take a silly idea and examine the consequences. The silly idea may springboard to another idea, and so on until you reach an idea that may not be so silly.

Developing the concept into a working story proposition.

Once you have found that great concept, it’s easy to get excited about it. But a concept alone isn’t enough to build a story on. At best it’s only likely to be one core element of your story, and you need five core elements working together. These are:

- The Protagonist’s Characterisation

- The Big Problem or Opportunity that sets up the central conflict

- Opposition – Antagonist Forces and Obstacles standing in his/her way

- A Story World.

- A Satisfying Resolution.

So for example, our idea about a dystopian society that forced children to compete to the death in a tournament is an idea or concept about the story world. We still need a main character (Katniss Everdeen), a problem she faces (survival), and antagonist(s) (the tributes, the games organisers, and President Snow) that get in her way, and a satisfying ending (she and Peeta both survive).

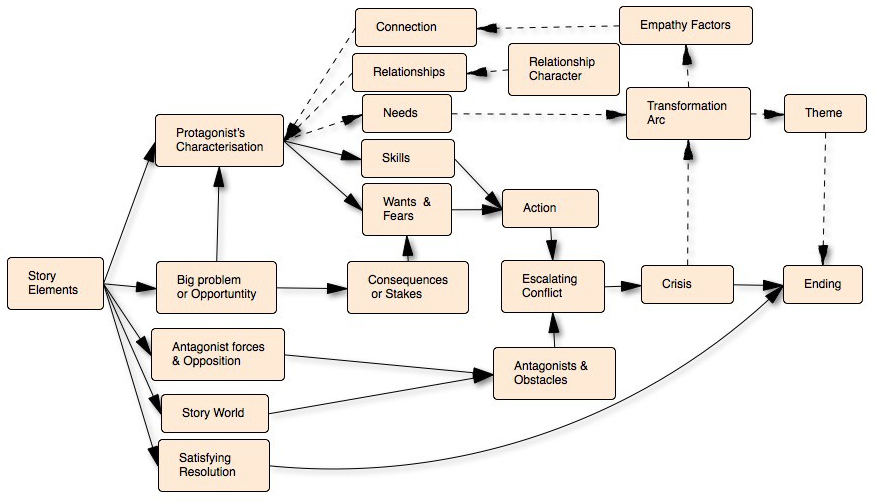

The relationship between these five core elements and their related factors can be set out as follows:

The Protagonist – Characterisation

All great stories have a protagonist that the reader can connect with. The reader doesn’t have to like the character, but they need to empathise with the struggle they are going through. Empathy factors are important. A reader is more likely to empathise with a character that is funny, clever, an underdog in jeopardy, selfless, resourceful and resolute. Katniss Everdeen ticks most of these boxes. But it’s possible to build empathy even with nasty characters if they have some redeeming qualities. For example, in Psycho, Hitchcock killed-off the main character half way through the movie and invited us to empathise with the killer, Norman Bates.

A key factor in connecting the reader to the main character is how he/she relates to other main characters and, in particular, the love interest, who will often play an important role in the main character’s inner story.

A character should never be perfect. Most have a flaw or emotional wound at the start of the story, and they learn from their experiences and change by the end of the story. This is the transformation arc, which is often related to the theme of the story. Not all stories have a transformation arc, but those that do are usually more satisfying for the reader.

The Big Problem or Opportunity

All stories are about a protagonist who desperately wants something or who wants to stop something from happening. It’s what drives the protagonist and what drives the plot forward.

The problem or opportunity is introduced to the protagonist in the first act by the story catalyst. The Catalyst is the point in time where the protagonist first becomes aware of the big problem or opportunity that will become the central conflict of the story. It is a jolt or shock that eventually causes the protagonist to act and changes his/her world forever. The late Blake Snyder describes catalysts as: telegrams, getting fired, catching the wife in bed with another man, the news you have three days to live, the knock on the door, the messenger.

Not any old problem/opportunity will suffice. The problem/opportunity needs to be difficult, and intractable, since once the problem/opportunity is resolved the story is over. Also, the extent of the problem may not be fully understood by the protagonist until the latter stages of the story. For example, Luke Skywalker, in Star Wars: A New Hope, initially wanted to take a couple of droids to Alderaan with the plans for the Death Star, but ended up rescuing a princess and blowing-up the Death Star. Erin Brokovich just wanted a job with Ed Masry’s law firm to support her kids, but ended up with a $2m bonus from a $330m legal settlement.

This escalation in the intensity of the problem/opportunity during the course of the story is part of a great story’s DNA. It creates reader tension about the protagonist’s uncertain future, which won’t be resolved until the climax.

For the reader to care, the protagonist’s problem should be life-changing and the consequences of failure life-threatening in a literal or figurative sense. For example, a young teenage girl volunteers to take her sister’s place in a brutal tournament where the tributes compete to the death (Hunger Games); or a New York cop trapped in a building with terrorists has to stop them blowing up the building and everyone in it (Die Hard).

Antagonist forces and opposition

All stories are about conflict: a struggle between what the protagonist wants and the obstacles that stand in his/her way. The stronger the antagonist forces are against him/her, the greater is the reader tension. Weak antagonists make for boring stories. Imagine Sherlock Holmes without Moriarty, or Batman without Joker. Strong antagonists bring out the best in heroes.

The obstacles that stand in the protagonist’s way may be physical/natural, supernatural, opposition from antagonists with different goals or competitors with the same goal, or it may be just his/her own shortcomings.

Story world and context

All stories take place in a story world – a setting, a time, a social environment with its own set of rules and conventions. Context will also be a factor in determining the genre: e.g. Sci-Fi, Fantasy, Historical fiction etc., or tone, as in a tragedy. One of the easiest ways to change the look and feel of a story is to change the context. For example, what would Hamlet or Macbeth look like in the 25th century?

Satisfying resolution

For a story to work it has to have an emotionally satisfying ending. But no one wants an ending that is too predictable. Some element of surprise is therefore necessary. Meeting these two conditions is difficult and requires a lot of thought and planning from the outset.

Playing with the Core Elements

It doesn’t matter where a writer starts with his muse. Any one of the five elements will do. But eventually he/she will need to address them all to find the shape of their new story. Once you have all five core elements of your story, you can flesh out the detail of the big moments of the plot. You will already know how the story starts and ends, and the opposition that the protagonist needs to overcome, which should be more than enough to give you the seeds of a good outline.

And lastly...

Still struggling to find that killer idea? Don’t despair. It’s important to understand that most stories are not new, but have been told a thousand times before. For example, Alien, Beowulf, Jaws are all what Blake Synder describes as ‘monster in the house’ stories. But to the reader or audience they feel very different. The Hunger Games and The Running Man are both stories about authoritarian societies televising a tournament to the death for entertainment, yet they feel very different. Similarly, West Side Story and Romeo and Juliet are the same story written in different social contexts.

The fact that many stories share similar patterns and features is not surprising. Christopher Book suggests that there are just seven basic plots to all stories. The late Blake Snyder stated that most Hollywood movies can be categorised under ten simple genre, each defined by three simple requirements. Chris Hoth and KC Moffat did a similar exercise to identify ten different story types based on the type of story tension, and they argue that most stories are a combination of one or more of these different story types.

So the trick is to find a combination of elements that makes your story feel new and interesting. If the story doesn’t feel new and exciting then perhaps modifying any one or more of the elements may give the story a different look and feel.

Pingback: Story Design — Characterisation | JMJ Williamson

Pingback: The Five Senses for writing. – The Fool's Journey